You may have heard of frontotemporal dementia eyes as a way to predict changes happening in the brain. This is a complex subject.

The following information can serve to help you understand the condition, the eyes’ involvement, and some of the concepts involved. However, you should always make sure to discuss the condition with your doctor if this is a serious concern for you or a loved one. Doctors can use other tools, such as memory tests, to help diagnose dementia.

The condition of frontotemporal dementia or degeneration affects the eyes in different ways. It causes an increase in attention to the eyes of faces seen, affects the movements of the eyes making them dysfunctional, and affects the ability to focus on traffic lights or targets. It can also affect the perception of lights in the periphery. These latter changes seriously impair driving.

If your loved one has frontotemporal dementia, look for the different symptoms and changes in eye function. Utilize the practitioners that can help you with this. And most importantly, keep looking for new solutions. Many different modalities and technologies have been released that could make a significant difference in your loved one’s ability to recover from the disease, or at least maintain present abilities.

What is the Frontal Lobe?

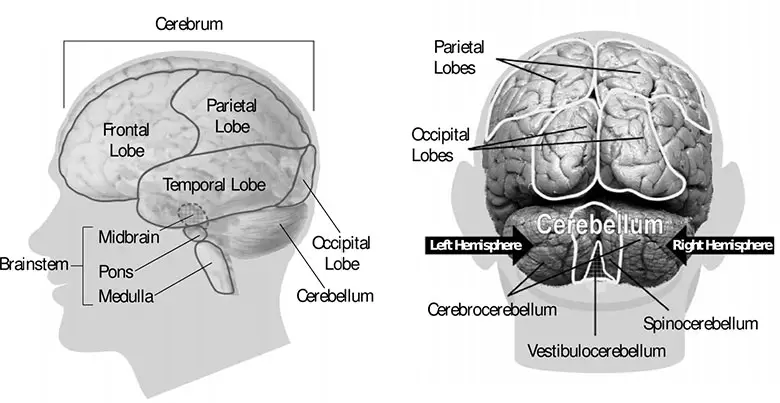

The frontal lobe is one of different parts of the brain. Four to the parts are called lobes. These four parts include the frontal lobe, parietal lobe, temporal lobe, and occipital lobe. The additional parts of the brain are the cerebrum, brainstem, and cerebellum.

The frontal lobe is found right behind the forehead. This area is the most common place of injury when there are traumatic brain injuries. This lobe is where most of our behavior and emotions are processed or originated; it’s considered the part of the brain for our personality. Your ability to plan, organize, initiate, monitor your own behavior and control what you do originates here. This lobe is also important for voluntary movement and expressive language.

Mood fluctuations, inability to focus on a task without distractions, difficulty problem solving, lacking the insight into difficulties, and not acting spontaneously in interactions with others are all problems that may be connected with the frontal lobe.

What is Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD)?

Frontotemporal dementia is not as common as Alzheimer’s disease in those over age 65. When Alzheimer’s disease hits someone in the age bracket of 45 to 65, it’s usually bvFTD or PPA.

Frontotemporal dementia is a group of different disorders. All the different disorders have one thing in common: progressive nerve cell loss in the frontal lobes or the temporal lobes. This damage to the nerve cells caused by frontotemporal dementia are due to some brain disorders involving the protein tau or another protein called TDP43.

FTD is also called frontotemporal disorders, frontotemporal degenerations, and frontal lobe disorders.

There are three different subtypes of FTD:

- bvFTD

- PPA

- ALS

The variant bvFTD is called this because it affects changes in personality and behavior. Usually this happens to people in their 50s and 60s but can start as early as the 20s and as late as their 80s. The personality changes occur because of changes in the nerve cells that affect judgment, empathy, foresight, and conduct.

The variant PPA stands for primary progressive aphasia. Aphasias usually affect language skills, writing, speaking and comprehension. This form shows itself when someone cannot understand or form sentences, or their speaking is labored, hesitant and doesn’t follow the usual grammar rules. PPA starts before age 65 but sometimes can start a lot later.

ALS stands for Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, which causes muscle wasting or weakness. It’s a motor neuron disease, also called Lou Gehrig’s disease. A motor neuron disease affects the motor neurons, the nerve cells that control the muscles of the body. ALS shows itself as either muscle stiffness, posture changes and difficulty walking and problems with the eye movements. It may also cause the arms to be stiff and sometimes they are not coordinated.

FTD is one of the most common causes of midlife dementia. It’s often misdiagnosed as Alzheimer’s or vice versa.

Difference between Alzheimer’s Disease and Frontotemporal Dementia

See the chart below for the differences between these two conditions.

| Alzheimer’s Disease | FTD | |

| Age | More common with increasing age | Hits people in the age 40-60 range |

| Memory loss | Prominent in early Alzheimer’s | Seen in advanced FTD cases |

| Behavior changes | Common as Alzheimer’s disease progresses (usually occur later) | First noticeable symptoms in bvFTD |

| Getting lost | Common | Not common |

| Speech problems | Trouble recalling names Trouble thinking of the right word Less difficulty making sense when they speak and understanding other people speak or reading | Trouble making sense of what others are saying when they speak and when reading |

| Hallucinations | Common in later stages | Not common at all |

| Delusions | Common in later stages | Not common at all |

38 Signs of Frontotemporal Dementia

The following list of signs and symptoms occur in those with frontotemporal dementia. Someone may not have all of the signs and symptoms, and it’s always a pattern of symptoms that a doctor is looking for in order to give him a clue about the diagnosis. In order to get an accurate diagnosis, one must see a competent neurologist who is skillful in diagnosing the condition and has much experience in evaluating those with different types of dementia.

- Muscle weakness

- Coordination problems

- Slow stiff movements similar to Parkinson’s disease

- Loss of balance

- Problems with eye movements

- May be dependent on a wheelchair or bedridden

- May have problems swallowing and chewing

- May have problems moving

- May have problems controlling bladder and/or bowels

- Physical changes in the skin that can lead to skin infections (may be due in part to lack of movement)

- May develop lung infections over time

- Agitation

- Irritability

- Depression

- Rude or insensitive

- Acting impulsively or rashly

- Lost interest in people and things

- Little drive and motivation

- Seems cold and selfish

- Repetitive behaviors that may include foot tapping, hand rubbing, and humming

- Walking the same route repetitively

- Poor table manners

- Compulsive eating, drinking or smoking

- Neglecting personal hygiene

- Loss of inhibitions

- Seems subdued

- Taste changes such as suddenly eating a lot of sweet foods

- Social isolation

- Difficulty understanding what others are saying

- Difficulty understanding what they are reading

- Using words incorrectly such as calling a dog a sheep

- Loss of vocabulary

- Repeating phrases over and over again

- Speech is hesitant

- Getting words in the wrong order

- Repeating things other people have said

- Eye changes

- When viewing faces, the patient is fixated more on the eyes than other parts of the face

Interestingly, many research studies have focused on how part of social problems related to different health disorders such as autism is dependent on how a person discriminates emotions by looking at the face.

If someone doesn’t pay attention to the eyes of the person they are viewing, they can’t read the person’s emotions. Someone with behavioral-variant frontotemporal dementia has well-established impairments in facial recognition and can’t see emotions that well. They also don’t scan the face that well but stay fixated on the eyes, compared to those without FTD. Researchers from Australia reported all this in their journal article in 2017 which appeared in the journal Behavioral Neurology.

Does Frontotemporal Dementia Affect Eyes?

Those with frontotemporal dementia do have changes with the physical working on their eyes as well. These changes have not generally been focused on by many practitioners.

Frontotemporal Dementia Eye Changes May Be Discovered

It turns out that the retina holds the key to diagnosing different types of dementia. In frontotemporal dementia, the thinning of the retina is in the outer parts of the retina. With Alzheimer’s disease and the disease ALS, the thinning in the retina is in other locations.

That’s what one researcher named Benjamin J. Kim, M.D. found out in 2017 that an inexpensive, non-invasive, eye-imaging technique created by the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. Kim is an assistant professor of Ophthalmology at Penn’s Scheie Eye Institute.

After reading all the available literature on nervous system disorders, they saw that the tau protein is expressed in photoreceptor cells. Based on this finding, they hypothesized that people who have tau brain pathology may have photoreceptor abnormalities.

Eye Movements May Give Insight into Different Diseases

Many illnesses may be seen first in the eyes before they are actually diagnosed. This is because the eyes are a part of the nervous system. Looking at them show the photoreceptors of the eyes, which reflect what’s happening in the nervous system.

Thus, if there is a disease that affects the nervous system, looking at the eyes may uncover the source of the problem quicker than regular diagnostic tests. When a saccade occurs, the image on the retina becomes blurred. When a person has ocular motor dysfunction, eye exercises are used to strengthen eye muscles’ ability to work together effectively.

The measurement of eye movements can also act as a tool to study cognition – memory, language, and spatial learning. For example, performing accurate, effective eye fixation and saccadic movement patterns, if performed badly, means there’s a potential problem of the oculomotor system (in the nervous system).

Saccadic movement means orienting your gaze towards a particular object, such as skimming a text or what happens during rapid eye movement sleep. It could also be looking at a light that starts blinking in your periphery or making an eye movement to a sound in the dark. Anticonvulsants, sedatives, and antidepressants that are sedating usually slow the saccadic movements as much as 50%.

How Eye Movements are Connected to the Brain

Eye movements originate from different parts of the brain. Here’s a table of the different types of movements

| Movement of the Eye | Brain Origination | Examples/Comments |

| Generation of saccadic movement (A red cross is presented in the middle of the screen for 10 seconds and the person has to look at the red cross without blinking.) | Superior colliculus, brainstem structures that directly innervate the eye muscles | Frontal eye field Supplementary eye field Parietal eye fields Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex |

| Voluntary pro-saccades toward a target (a red cross appears in the middle of the screen. After the person fixates on the cross, a green dot appears on either side of the target fixation cross.) | Frontal eye field | Some studies show that the time to generate a saccade is longer in someone with FTD |

| Reflexive saccades (this happens at night during REM sleep) | Parietal eye fields | |

| Anti-saccades (looking in opposite direction to a suddenly appearing target) | Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex Parietal eye field | |

| Smooth pursuit and fixation eye movements | Initially processed by extrastriatal cortical regions (V5 and medial superior temporal visual area), connecting to the posterior parietal cortex, FEF, ad SEF before being projected down to the pontine nuclei and cerebellum | These are primarily in the frontal and temporal regions. A range of oculomotor disturbances can be found if there are changes in this area. Those with FTD have abnormalities in this area. |

One example of how eye exams reveal diseases of the nervous system is that of finding thinning inner retina and a loss of optic nerve fibers in those who have Alzheimer’s, ALS, and Lewy-body dementia.

The researchers at Penn Frontotemporal Dementia Center compared 38 FTD patients to 44 subjects who did not have any neurodegenerative disease. The new test they used in the study was called spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT). In this test a light beam images tissues of the retina with micron-level resolution.

The thinning of the retina occurs because two parts of the outer retina – the outer nuclear layer and ellipsoid zone.

How FTD Affects Driving

When someone has frontotemporal dementia, the physical way that their eyes work may be altered. They may not be able to track movement with their eyes, see blinking lights in the periphery, or focus on one thing for 10 or 15 seconds. This can affect their driving.

Driving involves a lot of skills that must be coordinated at the same time. Decisions have to be made quickly, and if someone’s sense of judgment and physical gazing is off kilter, driving can become potentially dangerous. For example, one must be able to see traffic signals and traffic signs. While driving on a freeway, seeing a sign for an exit has to be done at the right time so that the driver can move over to the right to exit without becoming a threat to other drivers. Likewise, the car has to be steered in a way to minimize hitting objects and pedestrians.

Studies show that people with FTD do have significant difficulty with judgment of driving conditions and are at very high risk for injuring or killing themselves and others. Tests for whether or not it’s time to give up one’s driver’s license may include a driving simulator test first and then on-road driving.

Those with frontotemporal degeneration won’t be told initially to stop driving but as the condition progresses, giving up one’s driver’s license becomes inevitable. However, it’s difficult to give up one’s license. Thus, it’s important for the family to gradually limit the driving episodes during the early stages of disease. Providing rides to the patient for appointments and to the grocery store, etc. is the best. Caregivers can help out with this as well.